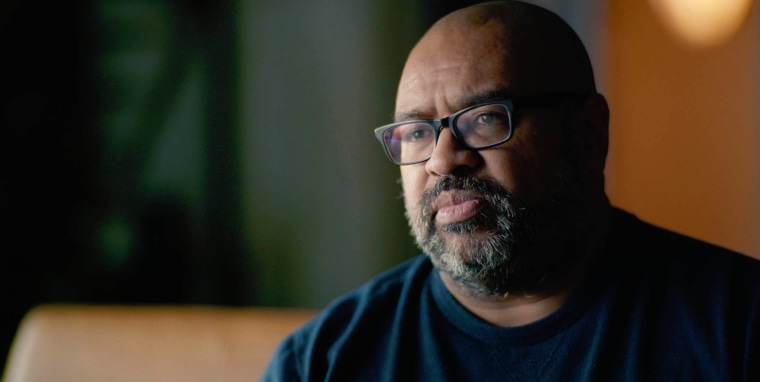

The Netflix documentary “Con Mum” is the story of one man’s dream-turned-nightmare. Graham Hornigold, a London-based pastry chef, grew up fantasizing about his birth mother. Then in 2020, he says in the documentary, a woman reached out saying she was the mother he never knew.

She said that she “never stopped loving” Hornigold, he says in the documentary. After a series of specific questions, Hornigold says he was convinced the woman knew enough details about his life to be his mother.

So, Hornigold and his pregnant wife, Heather Kaniuk, also a pastry chef, went to meet her. What came next is the story of “Con Mum.”

“You believe she is who she says she is. But she is a destroyer of lives,” Hornigold says in the documentary.

The rest of the documentary follows Hornigold's story, and how he says the woman claiming to be his long-lost mother conned him out of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

The woman claimed she was dying of cancer and wanted to leave her vast fortune to Hornigold, he says in the documentary. Swept up into her world, Hornigold became closer to the woman, ultimately staying with her when his wife and newborn went to New Zealand and helping her pay bills.

Eventually, Hornigold says in the documentary, he awakened to the woman's con. By then, he had given her money — a total of £300,000, he says in the documentary — and his marriage had ended.

The devastating final twist? A DNA test shown at the end of the documentary concludes that the woman was indeed Hornigold’s biological mother.

How did 'Con Mum' happen?

In an interview with TODAY.com, clinical psychologist Natalie Feinblatt, who specializes in trauma recovery for people who’ve left high-control groups and cults, says “anyone” is susceptible to scams — but Hornigold’s origin story left him particularly vulnerable.

Raised by a stepmother and father to whom he is no longer close, Hornigold says he often wondered about his mother growing up. “It’s quite painful, not knowing your mother. You haven’t got your mum,” he says in the documentary.

“Reuniting with a lost parent taps into deep psychological needs for connection and origin," Feinblatt says. "For someone who may already carry questions about identity or belonging, the desire to believe the story can override red flags. Scammers often exploit that window of vulnerability — not because the victim is naive or foolish, but because they’re human.”

In Hornigold’s case, Feinblatt says the con struck at the the “core” of his attachment system, an insight he echoes in the documentary.

“The realization kicks in that this woman is not who she says she is. Because of a cellular level need for acceptance and for a mother, I have been played,” Hornigold says in the documentary.

Dorcy Pruter, a therapist who specializes in parental reunification, tells TODAY.com the maternal connection likely blinded Hornigold to seeing the situation clearly.

"When someone comes along offering that relief, even if it’s wrapped in red flags, the heart can override the brain."

Dorcy Pruter

“People with unresolved childhood trauma or identity wounds are especially susceptible because they’re not just looking for answers — they’re looking for relief. And when someone comes along offering that relief, even if it’s wrapped in red flags, the heart can override the brain,” Pruter says.

For any victim of a scam, Feinblatt emphasizes the healing process can take a long time, because it requires “rebuilding a sense of safety and reality” beyond just recovering what has been lost.

Betrayal is accompanied by symptoms like anxiety, depression, hypervigilance and a sense of shame, coupled with the inability to trust instincts.

“People often describe feeling like the ground has dropped out from under them — confused, destabilized, and unsure who they can turn to,” Feinblatt says.

She sees value in documentaries like “Con Mum,” which show ordinary people being conned.

“There’s this myth that ‘only gullible people get scammed,’ when in reality, scams are often sophisticated, targeted and deeply emotional. Seeing real people go through these experiences helps normalize the pain of betrayal and shows that it can happen to anyone,” she says.

“Anybody can fall prey to this at the wrong place, at the wrong time. It just has to hit you in your in your vulnerable spot — and you’re in,” she continues. “A lot of people don’t like to look at it. It’s scary to consider.’