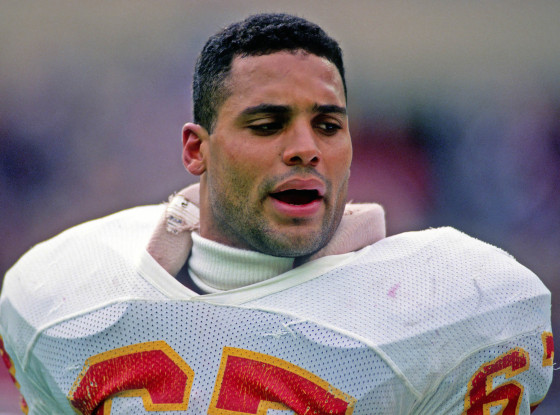

Art Still attributed his carpal tunnel, shoulder injuries, low back pain and neuropathy (a form of nerve damage) to decades of playing football — from high school through the pros as a defensive end for the Kansas City Chiefs in the 1970s and 1980s.

“That’s 20 years of football ... pounding my body,” Still, 69, of Kansas City, tells TODAY.com. “I thought those are just common things that would occur.”

After a wellness visit through a program with the NFL Players Association, Still underwent numerous tests. There, a doctor noticed Still experienced heart problems that seemed surprising based on his diet and exercise habits.

It eventually led to Still being diagnosed with ATTR amyloidosis, a rare genetic condition that causes heart problems, neuropathy, and ligament and tendon troubles.

Since his diagnosis in September 2023, Still has dedicated himself to increasing awareness, especially among former NFL players and other former professional athletes. Black people are more likely to develop the familial type of ATTR amyloidosis, which Still has.

“It may be a possibility that they might have amyloidosis,” Still says. “That’s one of the reasons why I’ve been trying to get some awareness out."

When the pain is a sign of something more

Still expected to have pain after playing professional football and didn't even realize that some of his injuries, from carpal tunnel to issues with his spine and low back, were a sign of something more.

“I figured that’s all from pounding, the physical side of the game,” he recalls. Every five years, Still participates in a medical evaluation hosted by the NFL Players Association, where he undergoes scans of his body and some routine testing. When he last had testing in August 2023, doctors felt puzzled by his atrial fibrillation (AFib), a condition which makes the upper chambers of his heart beat erratically.

“The doctors couldn’t figure out … why I’m having heart problems,” he says. “I eat a certain way, organically. I exercise every day and it’s pretty religious for me. I keep myself in good shape.”

Still has a long history of healthy eating. When played football, he received coverage for his fruit and vegetable heavy-diet.

“Back in the day, ‘Sports Illustrated,’ they had this article they called me ‘the fruit and nut man,’ but I eat fish and fowl,” he says. “Sometimes my wife thinks I’m too extreme and all, but I do all the research I can on nutrition, sleep and exercise.”

The doctor with the NFL Players Association discussed Still’s options, including medication or a procedure for the aFib, and asked him questions about his family history. Still mentioned his older brother James had a heart transplant but also experienced nerve damage and had knee and shoulder replacements.

“Then I explained to them about another brother of mine that needed a heart, my younger brother, and he has the same issues that I have,” Still recalls. “That’s when the doctor mentioned to me there might be a genetic defect that affects 1 out of 25 African Americans called amyloidosis.”

A paper in the Journal of Cardiac Failure notes that 1 out of 25 African Americans carry the mutation that can lead to ATTR amyloidosis, though being a carrier of a mutation does not mean that a person will develop the condition.

There is also another type of ATTR amyloidosis referred to as the wild type, which occurs for no known reason, according to Cleveland Clinic. It's more likely in elderly individuals and men, thought it does affect women too.

After the doctor suggested he had amyloidosis, Still met with Dr. Brett Sperry, a cardiologist and director of the cardiac amyloidosis program at St. Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute in Kansas City.

Routine tests confirmed that Still had it. At first, Still felt stunned by the diagnosis.

“I’ve learned and come to appreciate that you can have (health conditions) that you don’t have … control over,” he says. “But it’s how you react to it (that makes a difference).”

Amyloidosis

Amyloidosis occurs when the proteins in the body become sticky and begin to clump together, Sperry says. In the brain, there's a type of amyloidosis that people know as Alzheimer’s disease. In the heart, it can be hereditary or wild type ATTR amyloidosis.

“(It’s) like an aging disease of the heart where this protein gets stuck in there and causes the heart to be stiff and not work as efficiently as it should,” Sperry tells TODAY.com.

Symptoms of amyloidosis include both cardiovascular signs and others that seem as if they would be unrelated, such as carpal tunnel syndrome. Signs include:

- Shortness of breath

- Irregular heart beats

- Fatigue

- Swelling

- Neuropathy in the hands and feet

- Bicep tendon rupture

- Shoulder problems/rotator cuff issues

- Carpal tunnel

- Back pain

- Spinal stenosis

“About half the people will have carpal tunnel syndrome,” Sperry explains. “Not everyone with carpal tunnel syndrome has amyloidosis. It’s about 10% of the people that have carpal tunnel syndrome who are over 60 actually have amyloidosis.”

The reason people experience nerve and ligament troubles is the sticky proteins get tangled up in the nerves and ligaments, Sperry explains.

Both types of amyloidosis occur much more often in men.

“About 90% of the people who have this are men for some reason. We don’t know why,” Sperry says. “It also seems to affect people who were very active in their life. Again, we don’t know why.”

Early diagnosis and treatment for amyloidosis remains key. But lack of the awareness of the condition can mean many go undiagnosed for a long time. It’s also a rare disease, so many doctors do not consider it.

“If you get diagnosed early, there are treatments (that) can stabilize things, just stop the progression … and prevent worsening of any heart disease or nerve disease,” Sperry says. “(But) once the amyloidosis proteins get stuck in the heart, they’re extremely strong, bond very tightly together, and we don’t have anything right now that can release those.”

In Still’s case, the screening helped him to get an early diagnosis, which means his health remains relatively stable.

“He’s at such a high level of physical fitness to start off with that even if he dropped off 10-20%, he’s still functioning higher (than most),” Sperry says. “He does a good job. He’s been on a medication to stabilize and prevent worsening disease.”

Racial disparities in health care can contribute to later diagnosis of ATTR amyloidosis, especially in some regions of the country, Sperry notes.

“Rates of diagnosis are very low in some of the more rural areas and especially in the rural areas where there is a larger Black population,” he says. “They should probably have the most number of patients. They actually have some of the lowest rates.”

But the reasons for this are complex, Sperry says. Patients might not seek medical care, and there are fewer specialists in rural areas who are able to diagnosis the condition.

“There definitely are regional disparities in the U.S.,” he says. “Some of it’s related to race. I think some of it is related to the region of the country and access to health care.”

Spreading the word

Since his diagnosis, Still has been dedicated to raising awareness of amyloidosis.

“The earlier the detection of it, you might not get to the heart problems,” he says. “That’s part of the process. If you see some symptoms, talk to your doctor.”

Locally, Still visits community centers, YMCAs and senior living centers to talk about his condition. He recently visited New Jersey to speak about amyloidosis with a group of Black nurses, and he spoke about it with former Chief’s players.

He hopes that his awareness campaign encourages people to be “proactive (about) getting checked for it (because) it makes a world of difference.”

Having the support of his family — his wife, 11 children and soon to be 25 grandchildren — has helped Still cope with his diagnosis.

“There’s some things unforeseen that happen in our life beyond our control,” he says. “When you help others, you heal yourself.”