A patient who'd been hospitalized in Louisiana with severe illness from H5N1 bird flu has died — the first human death from this type of avian influenza in the U.S., the Louisiana Department of Health announced on Monday, Jan. 6.

The person, whose identity has not been released, was over the age of 65 and had underlying medical conditions, the statement noted. The patient contracted H5N1 "after exposure to a combination of a non-commercial backyard flock and wild birds," the department said.

An extensive public health investigation found no other H5N1 cases nor evidence of person-to-person transmission.

While the state health department said the risk to the public remains low, the death is raising concern over whether the bird flu could lead to another pandemic or lockdown.

H5N1 has infected dozens of people in the U.S. and spread to 10 states and Canada this year.

California has declared a state of emergency over the spread of the virus in its dairy cows.

There hasn't been any person-to-person transmission of bird flu and the current public health risk is low, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention emphasizes.

But a single mutation of the virus strain now widely infecting dairy cattle could allow it to spread in humans and "could be an indicator of human pandemic risk," according to research published in December in the journal Science.

"The longer this virus circulates unchecked, the higher the likelihood it will acquire the mutations needed to cause a pandemic," Dr. Les Sims, a veterinary expert in Asia, told the American Veterinary Medical Association.

"We need to act urgently to prevent this scenario."

Bird flu deadly case in Louisiana

A genetic analysis of samples from the patient who died in Louisiana showed mutations that may make it easier to spread to people, the CDC reported in late December.

But a “sporadic case” of severe H5N1 bird flu illness is not unexpected, the CDC said in a news release.

"Previously, the majority of cases of H5N1 in the United States presented with mild illness, such as conjunctivitis, and mild respiratory symptoms and fully recovered," Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said during a media briefing on Dec. 18.

"It's notable that this is the first human case of H5N1 associated with a backyard or noncommercial flock."

Investigators believe exposure to the virus happened on the Louisiana patient's property, Daskalakis added. He declined to comment about the person's symptoms.

Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious disease physician at UCSF Health, said he was very concerned when news about the severe case in Louisiana was first announced in December.

"I'm not saying this is a cause for panic right now. But in the medium-term, I think all the signs are pointing to the temperature rising with bird flu in terms of its potential impact on humans," Chin-Hong told NBC News.

Bird flu in humans

Almost all human bird flu patients in the U.S. have had contact with infected animals and when doctors analyzed 45 of those cases, they found all the patients had mild illness that lasted for a few days, according to a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in late December.

When it came to symptoms, 93% of the infected people had conjunctivitis, 49% had a fever and 36% had respiratory issues.

Most patients received oseltamivir, an antiviral medication also known as Tamiflu.

Bird flu critical illness in Canadian teen

New details have emerged about a Canadian teen — that country’s first bird flu patient — who was left in critical condition after contracting H5N1 last fall.

The 13-year-old girl, who has obesity and a history of mild asthma, first came to an emergency room in British Columbia in early November with conjunctivitis (pink eye) in both eyes and a fever, according to a case report published with her family’s permission in The New England Journal of Medicine at the end of December.

She was sent home, but then developed a cough, vomiting and diarrhea, and returned to the emergency room three days later in respiratory distress.

The girl was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit at British Columbia Children’s Hospital with respiratory failure, pneumonia, acute kidney injury and other problems.

She developed acute respiratory distress syndrome — a life-threatening lung injury — and had to be intubated and placed on a form of life support.

The young patient received three antiviral medications and other therapy. As she improved, her breathing tube was removed at the end of November.

The girl is no longer infectious and no longer requires supplemental oxygen, according to additional information posted by The New England Journal of Medicine.

It’s still unknown how she was exposed to bird flu.

The H5N1 virus “can cause severe human illness,” the doctors and experts who authored the case report wrote.

“Evidence for changes to HA [a protein in the virus] that may increase binding to human airway receptors is worrisome.”

Outside experts were concerned, too.

“If you look at how severe this infection was, I think it’s pretty fair to say that this is a terrible virus,” Dr. Isaac Bogoch, an infectious disease specialist at Toronto General Hospital, told CBC News.

Raw milk recall amid bird flu outbreak

California has announced a recall of raw milk after the virus was found in some products from Fresno’s Raw Farm, LLC. Another recall covers raw milk from Valley Milk Simply Bottled of Stanislaus County.

Raw milk, which is not pasteurized, can expose people to germs and lead to serious health risks, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has warned.

Consumers don’t realize the raw milk they buy is not from a single cow, but pooled from many cows, says Dr. Ian Lipkin, an expert on emerging viral threats.

“If one cow in that group has H5N1, then it gets distributed to many, many more people,” Lipkin, professor of epidemiology at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, tells TODAY.com. “It’s not a good situation.”

Drinking or accidentally inhaling droplets from raw milk containing bird flu virus may lead to illness, California health officials warn. So can touching your face after touching the contaminated milk.

Pasteurized milk is safe to drink because pasteurization kills the bird flu virus and other germs, the experts emphasize.

The state is home to 37 human cases of bird flu, or more than half of the country’s total, according to the CDC. None are linked to raw milk.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture has ordered testing of milk for the virus, requiring that raw milk samples nationwide be collected and shared with the agency.

What is bird flu?

Like people, birds can get the flu, and the avian influenza viruses that make birds sick can sometimes infect other animals like cows and, rarely, people, the National Library of Medicine explains.

H5 is one family of bird flu viruses. It has caused widespread flu in wild birds worldwide and is causing outbreaks in poultry and U.S. dairy cows, the CDC notes. Some farm workers exposed to those animals have also gotten sick.

H5 has nine subtypes, including H5N1, the strain responsible for the recent illnesses.

Could bird flu cause the next pandemic? Here’s what to know about symptoms, how to protect yourself and more.

Bird flu in the USA: Which states have cases?

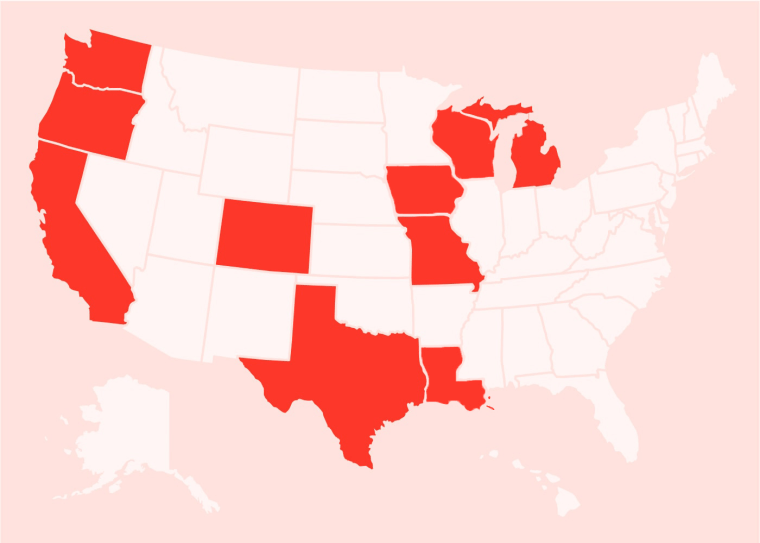

There have been 66 confirmed human cases in 10 states in the U.S. since the 2024 outbreak, according to the CDC.

They’ve been reported in:

- California: 37 cases

- Colorado: 10 cases

- Iowa: 1 case

- Louisiana: 1 case

- Michigan: 2 cases

- Missouri: 1 case

- Oregon: 1 case

- Texas: 1 case

- Washington state: 11 cases

- Wisconsin: 1 case

Probable cases have also been reported in Arizona and Delaware, though the CDC was unable to confirm the presence of H5N1 in those samples in its laboratory.

Almost all U.S. patients had contact with infected cattle, poultry, backyard flocks, wild birds or other animals.

But two cases in North America are getting particular attention because it’s not known how they were exposed to the virus: the teenager in Canada and a person in Missouri.

There’s been no confirmed person-to-person spread.

Bird flu outbreak

“We do have an outbreak of human infections of H5N1,” says Dr. Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and a spokesperson for the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

The current public health risk from H5 bird flu is low, the CDC says. Its flu monitoring systems currently show no signs of unusual flu activity in people, including the H5N1 virus, or any unusual flu-related trends in emergency department visits.

But the agency is “watching the situation carefully” — as are experts in the field.

Lipkin calls it an important health concern.

“Emerging infectious diseases are unpredictable. If you told me 20 years ago that we were going to have major problems with coronaviruses, I wouldn’t have predicted that,” Lipkin says.

“So nobody knows what’s going to happen with this particular flu.”

Human infection with bird flu can happen when the virus gets into a person’s eyes, nose or mouth, or is inhaled, according to the CDC. The illness can range from mild to severe and can be deadly.

Human H5N1 cases in the U.S. have been relatively mild, perhaps because people are mostly getting infected through their eyes, Adalja notes.

It might happen when a dairy worker is milking an infected cow and gets squirted in the face with the milk, for example.

“You’re getting infected from the eyes rather through the respiratory route,” Adalja tells TODAY.com. That may be “less risky than respiratory inhalation” of the virus, he adds, when it can go to the lungs.

Is bird flu a global health emergency?

No, the World Health Organization doesn’t currently categorize the bird flu outbreak as a global health emergency. Outbreaks that do fall into this category include COVID-19, cholera, dengue, Marburg virus and mpox.

The state of California recently declared a state of emergency over bird flu.

Could bird flu turn into a pandemic?

Experts say it’s unlikely this particular strain of bird flu would lead to a pandemic because it doesn’t have the ability to spread efficiently between people.

H5N1 has been infecting humans since 1997, so it’s had time to evolve, but still doesn’t easily jump from person to person, Adalja points out.

“I don’t think that this is the highest-risk bird flu strain,” he says. “You can’t say the risk is zero. But of the bird flu viruses, it’s lower risk.”

Lipkin had a similar take.

“Nobody ever wants to say never because you can be wrong,” he cautions. “Could this virus evolve to become more transmissible? Yes. Has it done so thus far? No. Do I personally think it’s going to be responsible for the next pandemic? No. Could it be? Yes.”

Since there are many different avian influenza strains, one of them may be able to cause a pandemic in the future, Adalja adds.

The bird flu strain he’s more worried about as a pandemic risk is H7N9, which was first reported in humans in China in 2013 and expanded to more than 1,500 people by 2017. This virus also doesn’t spread easily from person to person, but when people do get infected, most become severely ill, the World Health Organization warns.

The most recent human H7N9 virus infection was reported in China in 2019, according to the CDC.

Could there be a lockdown due to bird flu?

A lockdown due to bird flu is not likely for this strain, since H5N1 isn’t posing a threat to the general public, both experts say.

If that were to change, people should realize lockdowns, like those during COVID-19, are not the “go-to measure” for an infectious disease emergency, Adalja says, calling them “very blunt tools.”

Instead, proactive measures — such as more aggressive testing of farm animals — will allow health officials to be much more precise when it comes to stopping the spread of infection, he notes.

When it comes to lockdowns, there’s also the question of how far authorities are willing to go.

“If H5N1 were to become a major health problem, we would have to talk about (containment),” Lipkin says. “But I don’t think that this incoming administration is going to be amenable to that.”

What is the treatment for bird flu?

It’s oseltamivir, also known as Tamiflu, the same antiviral medication used for ordinary cases of flu.

It’s important to start that drug as soon as possible after symptoms start for it to have an impact, Lipkin says. Some close contacts of people who’ve been infected with H5N1 have also received the drug as a precautionary measure to prevent infection.

Is there a bird flu vaccine?

Four vaccine candidates for dairy cows have been approved for field trials, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

In poultry, four potential bird flu vaccines began to be tested in 2023, Reuters reported.

When it comes to humans, the CDC says the U.S. government is developing vaccines against H5N1 viruses “in case they are needed.”

The agency adds it has H5 candidate vaccine viruses that could be used to produce a vaccine for people, and preliminary analysis shows “they are expected to provide good protection” against H5N1.

There are also some vaccines in the strategic national stockpile that are closely — if not exactly — matched to this particular strain of bird flu, Adalja says.

“There are efforts to make more updated vaccines. But there is no widespread vaccination program being initiated against H5N1 at this time in the U.S.,” he notes.

In the summer of 2024, Finland became the first country in the world to offer bird flu vaccinations for people at risk of exposure, including workers at fur and poultry farms.

Finland bought vaccines for 10,000 people, each requiring two injections, Reuters reported.

In December 2024, the United Kingdom announced it had secured more than 5 million doses of human H5 influenza vaccine. The purchase will “boost the country’s resilience in the event of a possible H5 influenza pandemic,” the UK Health Security Agency said in a statement.

What does bird flu do to humans?

Bird flu in humans can cause no symptoms, or anywhere from mild to severe symptoms, according to the CDC. Most people who have been infected with bird flu have reported mild symptoms, such as eye infections and flu-like symptoms, according to Yale Medicine.

The CDC lists the following bird flu symptoms:

- Eye redness

- Mild flu-like upper respiratory symptoms

- Fever or feeling feverish

- Cough

- Sore throat

- Runny or stuffy nose

- Muscle or body aches

- Headaches

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Pneumonia requiring hospitalization

- Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting or seizures (these are less common symptoms).

Is bird flu deadly?

Yes, bird flu can be deadly.

The mortality rate of bird flu in humans, based on the roughly 900 confirmed people infected with the virus between 2003 and 2024, is about 50%, according to Yale Medicine.

However, it's likely that many more people have been infected without knowing it because they had no or mild symptoms, so the mortality rate could be much lower than 50%. And the mortality rate would likely drop even further if treatment and vaccines were made more widely available, should human-to-human spread start to occur.

How does bird flu spread to humans?

There are several ways the bird flu virus can spread from animals to people, according to the CDC:

- Touching something contaminated with the virus and then touching your nose, eyes or mouth

- A liquid that contains bird flu virus splashing into your eyes (such as raw milk from an infected cow)

- Eating, drinking or breathing in droplets containing the virus

How to protect from bird flu

The people most at risk for H5N1 bird flu are dairy and poultry workers who might be around infected animals, Adalja says. They should wear personal protective equipment while working on farms affected by the virus, the CDC advises.

When it comes to the general public, “don’t consume raw milk, full stop” since H5N1 is viable in it, Lipkin says. Pasteurized milk can eliminate the risk of infection, he notes.

Properly cooked chicken is safe to eat, but wash your hands with soap and water after handling raw chicken, he adds.

It might be wise to skip petting zoos or events where you can learn how to milk a cow, Adalja adds.

Avoid direct contact with sick or dead wild birds, poultry and other animals, the CDC advises.