Standing in the airport fidgeting with my plastic, TV reporter earpiece, my camera crew is setting up to interview a traveler when she fills the brief silence by asking, “How does your wife like New York?”

It’s a small conversational crossroads I’ve faced many times. Is it easier for this quick interview to just not correct her that I have a husband instead of a wife? Still, I find myself answering in milliseconds, “My husband is still adjusting, I think. He does miss driving and good Tex-Mex though.”

“Oh, sorry! Husband. My own husband doesn’t even have a driver’s license. Never needed one,” she says, continuing the conversation without much of a pause.

With the camera’s red light on, I ask about her travel delays. Then when we’re finished recording, she says with a slight chuckle, “I actually didn’t fly until I was in my 40s. Grew up dirt poor. Just didn’t want to say that on camera.”

I find myself faced with another coming out.

“You’re not alone there. I actually grew up poor too. My first plane ride was in my 30s, but I had to use about three different credit cards to pay for it. You probably made better choices than I did.”

We laugh a bit more, I thank her for chatting and she disappears out of the sliding glass door.

But this airport encounter, though brief, stuck with me — a reminder that honesty, even about something seemingly inconsequential like marital status or family background, could make me feel so fond of an absolute stranger. It was a sense of simple connection that I’d spent years robbing myself of with constant pretense, trying to not stand out.

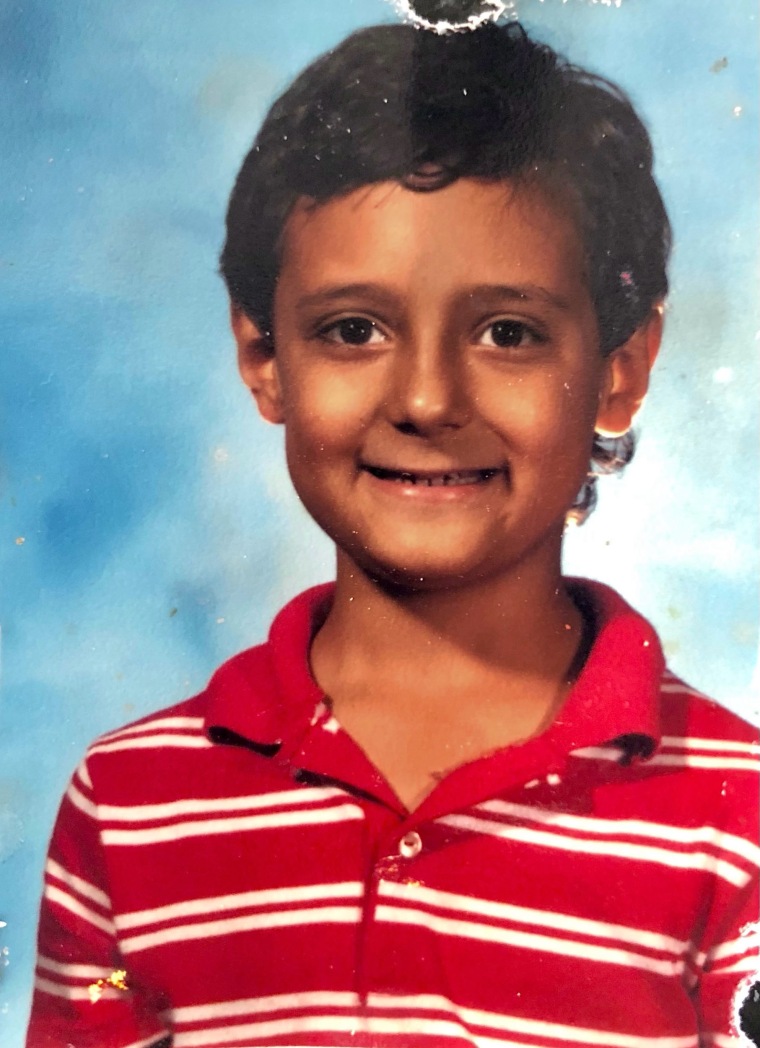

Flipping through the scant photos that survived my roach-infested childhood, I can’t help but smile at the greasy-haired kid staring back at me. He had no idea the parts of himself he hated would turn out to be exactly what saved him. What I wanted most back then was to be normal — to fit in. No matter how hard I tried and schemed, I never quite got there. My family and I always seemed to stand out. I was usually one of only a few Latino students in my classes. It was much more than that, though. While other kids were getting dropped off at school by minivans glazed in blue, the jalopies that I arrived in were decorated with rust spots and cracked windows. And when most classmates were wearing crisp, new back-to-school clothes, I was washing my own clothes in the bathroom sink and using a permanent marker to try to resuscitate my faded, formerly black jeans.

Hiding many of these differences was just not possible. But that didn’t keep me from trying — scheming — to hide who I really was. Tall tales about my “wealthy parents” forcing me to wear dirty, ragged clothes to keep me humble didn’t fool classmates for very long. So, I reverted to secrecy and aloofness. Those were some of the earliest things I learned at home — my first language in a way. It’s not something I was explicitly taught, like how to tie my shoes. These were skills I picked up by watching my parents. When someone came to the front door, I learned to freeze in place so the visitor would think no one was home. This was all an effort, to varying degrees of success, to hide what was going on behind that flimsy door.

Trying to explain the conditions of the house seems simple. We had five or six dogs that never went outside. They used the carpet as their bathroom. And the fast food trash piled up over any surface that could hold it. The predictable roach infestation followed. My mom, who ended up passing away while I was in college, had mental health struggles she never truly got help for. My dad worked as a big rig driver. That left my siblings and me to navigate the chaos on our own.

But then around fifth grade, a new secret I learned about myself made me feel even more alone. Just as many of the other boys started to show interest in girls, I figured out I was gay. I fought it. I tried to will myself straight. I tried to pray myself “normal.” When that didn’t work, I resorted to what felt most natural to me anyway: I decided to hide it.

Projecting this false self into the world every waking moment wasted so much time and energy. And worse, it kept me perpetually at a distance from everyone else. There was always an invisible wall manifested in lies and half-truths. I see that now in these photos showing younger me’s big brown eyes. He was so full of worry and doubt that no kid should have had to carry.

Of course, it wasn’t until I shared these secrets that I was able to wriggle out from under their weight and finally breathe. In high school, I told my best friend about the situation at home. He told me it wasn’t my fault. After I got my first job in news, I told my sister I was gay. She told me she’d already figured that out, and we grew even closer. Coming out freed me. I finally gave myself permission to meet more LGBTQ+ people, and I learned that queer joy is even more powerful than queer sorrow.

Coming out freed me. I finally gave myself permission to meet more LGBTQ+ people, and I learned that queer joy is even more powerful than queer sorrow.

It wasn’t until I stopped trying to blend in that I realized these differences are what gave me the tools I needed to make it. Being an outsider proved to be a gift in disguise. If you’re lucky, feeling isolated can lead to self-reliance, and that helped me navigate my way out of my upbringing. And now covering the news, I get to connect with not only other LGBTQ+ people in their own lived experiences but also others who exist on the margins — the overlooked, the people who feel different. I have the honor of speaking with them in a way others may not be able to. Like interviewing Kate and Trish Varnum, the first same-sex couple to marry in Iowa, and truly understanding their fresh fears about anti-LGBTQ+ legislative proposals targeting their union. Or reporting on a surge of GoFundMe campaigns raising money for same-sex couples’ fertility care, because some insurance companies use definitions that leave them without adequate coverage.

It turns out, all those things I spent so much time and energy resisting and hiding as a kid have given me superpowers as an adult. And the radioactive spider? That turned out to be simple honesty, allowing me to spin webs of connection. Now, with each truth I share, with each story I tell, I can help bridge the divide between the margins and the blinding mainstream.

Sure, it’s not always easy. There were a lot of ups and downs along the way, like when I dropped out of high school, struggled with depression and constantly fought to make ends meet. And the flip side of that self-reliance sometimes manifests in distancing myself from those who love me. That’s something I’m still working on, and in some ways maybe I always will be.

Looking back at the grimy kid in these tattered photos, I see that while he might not have realized it, he was always meant to tell tales. Not ones to hide who he was or how he struggled, but about how he survived. And of finding the extraordinary strength in embracing the beautiful mess of who we truly are.